What if a demon crept after you into your loneliest loneliness some day or night, and said to you: "This life, as you live it at present, and have lived it, you must live it once more, and also innumerable times; and there will be nothing new in it, but every pain and every joy and every thought and every sigh, and all the unspeakably small and great in thy life must come to you again… Would you not throw yourself down and gnash your teeth, and curse the demon that so spoke? Or have you once experienced a tremendous moment in which you would answer him: "You are a God, and never did I hear anything so divine!"

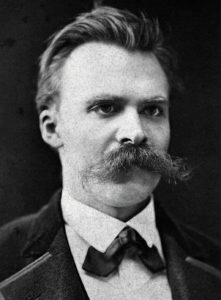

-Friedrich Nietzsche, The Gay Science, 341

If the universe were infinitely old and infinitely large, and would continue on and on forever, then everything that could possibly happen would happen, somewhere, sometime. In all that vastness, there would be an infinite number of galaxies, and in those galaxies an infinite number of stars. An infinite number of planets would orbit them, and some of those would have to be very much like earth. If the universe really were endless (and this wasn't an unthinkable possibility in Nietzsche's day, apparently, although cosmologists now think differently) some of those planets would, just by random chance, end up being exactly like the earth, with their own versions of you, living your exact life.

In fact, if the universe really were endless, there would be an infinite number of exactly-earths with an exactly-you on them. Your life, precisely as it is, has been and will be lived an infinite number of times, with no changes and no improvements.

And what, Nietzsche wants to know, do you think of that?

This is the ETERNAL RETURN OF THE SAME. (It's also known as eternal recurrence, but that doesn't have such a nice ring to it.)

When I run this thought experiment, my mind goes immediately to planets that are a little different from earth – the one where I'm richer, more popular, or have the ability to fly – but that's not the goal Nietzsche sets for us here. The variations that live on those hypothetical worlds aren’t exactly me. The life I've lived has both successes and failures, points of pride and moments of embarrassment, victories, guilts, and defeats.

What would it take to want that all over again?

A View of the World

This question is worth exploring because it grows out of an assumption about the way the universe works that may be true, but it isn't often considered. Every approach to the good life has to start with some idea about how well-suited we are to living on earth. They fall on a spectrum, from those that see the world primarily as a source of happiness, to those that envision a place of inevitable suffering.

Some thinkers – philosophers, psychologists, and happiness gurus among others – think of the world as a benevolent place. Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716) believed that some amount of evil was necessary for good to flourish; since we can't live in a perfect world, we live in the best of all possible worlds.[i] More recently, something similar has been taken up by proponents of the law of attraction, like Rhonda Byrne who published the well-known, century-old idea as The Secret, arguing that the world is waiting to grant our wishes if we can just figure out how to wish them on the right frequency.

Others see the world as basically friendly, but we have to tweak it to a greater or lesser degree to suit our needs. Many Enlightenment philosophers like John Locke saw it this way, as do some contemporary positive psychologists like Shawn Achor.

At the far end of the spectrum are the thinkers who see a fundamental mismatch between human lives and the world they inhabit. "Life is suffering" is the Buddha's first Noble Truth. There is no way to change the world to prevent it. As different as Nietzsche is from the Buddha, they both share the view that humans are not inherently well equipped to deal with the blows reality can deal us, and that it takes work to change into someone who is.[ii]

So many approaches to happiness involve looking for ways to see the good in things. But this leaves a gaping philosophical hole: what happens if there is no good in a situation, or deciding that there is would involve compromising one's values or identity? People like Achor and Leibniz have no answer for this.

How Does it Work?

For Nietzsche, the idea of the eternal return represents the way to measure one's acceptance of the pain that comes with human life. Only when a person can be comfortable with the idea that their entire existence will be relived over and over without change, then will they have accepted reality as it is.

The eternal return thought experiment is a measure of acceptance, but it's not a method for getting there. Nietzsche makes some suggestions, but it's hard to sort out his meaning (especially, I suspect, in English translated from the original German aphorisms). But I've come across a number of theories about what he had in mind.

As I read it – and this is filtered through my own 21st century, psychanthropologically-informed lens – the eternal return is about seeing your life as a whole, and as a whole life worth living. Who you are is a reflection of the life you've lived. It's not just the things you want to remember – it's the dark, the sad, and the shameful as well. To truly accept who you are today involves embracing – not just accepting – everything that contributed to it.

And this is coming from a philosophy that sees the world as a dark place, with experiences that can't always be redeemed, reinterpreted or set aside. Being able to welcome even those terrible experiences simply because they make you who you are – even to the point of being willing to repeat them an infinite number of times – is the mark of a life will lived.

By seeing them as contributing to the great project of making you you, it takes events that appear to be senseless and painful and gives them meaning, fitting them into the order of your life.

It's a tall order from a dark philosophy. But at times, seeking happiness through the darkest of lenses is the right thing – for some, the only thing – to do.

If you enjoyed reading this, please help me out by passing it on to other people who might appreciate it, sharing it through e-mail or your favorite social media platform. You can also follow me on Facebook and Twitter (@s_g_Carlisle).

[i] The Romantic Ethic and the Spirit of Modern Consumerism p. 114.

[ii] See, for example, Kain, 2007.

Citations:

Campbell, Colin

1987 The Romantic Ethic and the Spirit of Modern Consumerism. London: Basil Blackwell Ltd.

Kain, Phiip

2007 Nietzsche, Eternal Recurrence, and the Horror of Existence. The Journal of Nietzsche Studies (33) 49-63.

Nietzsche, Friedrich

1974 The Gay Science: With a Prelude in Rhymes and an Appendix of Songs. New York: Vintage Books,

The photograph of Friedrich Nietzsche at top is in the public domain. It was taken by Friedrich Hartmann (1822-1902) in Basel - https://s-media-cache-ak0.pinimg.com/originals/04/10/0b/04100baec90c105729b47f33c371476b.jpg