Not feasible.

At least not in the absolute sense. A few people appear to have managed it - some A-list movie stars and ex-presidents. As it turns out, the unfeasibility is part of the point.

For the rest of us, a certain level of compromise is necessary. But if those compromises are comfortable, then "having it all" becomes "having enough," and people hardly notice the difference.

The idea of HAVING IT ALL is used in different ways in different contexts, but in general it refers to the idea of having more than one kind of happiness. These usually include things like:

- Financial success

- Rewarding family life

- Healthy attractiveness

- Strong friendships and social connections

- And an adventurous, storied lifestyle

A hundred and fifty years ago, our ancestors would have been happy enough just to make it through the end of the month. What gives us the temerity not just to want to survive, not just to prosper, but to actually have it all? Seems a bit entitled, no?

But that has been a growing part of the American cultural context for centuries.

A Little Background

The first thing to notice about the phrase is that it's about having. Why do we talk about this, rather than Being it all, or Experiencing it all, or maybe even Feeling it all? It's important to remember that having isn't actually the most effective way to find happiness. There is a limit to the pleasure that material goods can bring. Research suggests that people find engaging experiences more worthwhile than possessing things.[i]

The language here – with the emphasis on having – gives us a clue as to where this idea came from, and how it gained a foothold in so many people's minds. Alexis de Tocqueville – the French nobleman whose visit to the US in 1831 served as the basis for his book, Democracy in America – explores what happens when people live in a society in which they view themselves as equal to everyone else. It was especially interesting to this Frenchman living in the years after the Revolution – he could see that the hierarchy was going to have to give way to something else, and he wanted to know what. He writes that in France:

The serf considered his inferiority as an effect of the immutable order of nature. Consequently, a sort of goodwill was established between classes so differently favoured by fortune. One found inequality in society, but men’s souls were not degraded thereby.[ii]

But that didn't apply in the US. The idea that people were equal, he suggests, drove them to attempt to become more equal than the people around them, leading to a sort of keeping-up-with-the-Jonses way of measuring self-worth. He had this to say about the America character:

At first sight there is something surprising in this strange unrest of so many happy men, restless in the midst of abundance. … Their taste for physical gratifications must be regarded as the original source of that secret inquietude which the actions of the Americans betray, and of that inconstancy of which they afford fresh examples every day. He who has set his heart exclusively upon the pursuit of worldly welfare is always in a hurry, for he has but a limited time at his disposal to reach it, to grasp it, and to enjoy it.[iii]

This force, combined with the idea that there was a practical, material solution for every problem, compelled the Americans he met to associate having with happiness.

But this is only part of the solution. As the 19th century wore on, the ways that people thought about consumption changed. As the advertising industry developed it played on this American proclivity; the industry grew, in large part, out of the patent medicine trade, which was founded on the idea that the best way to get people to buy was to convince them that they had a problem that could only be fixed by whatever the manufacturers had to offer. The fact that these needs were illusory got lost in the shuffle.

You can find a fuller explanation for this in the discussion of retail therapy; having it all is retail therapy taken to its logical conclusion. The things that would allow you to have it all – things that can give you status, things that can make your family happier and work more efficient, things that make your body more healthy and your life more exciting – can all be bought and sold. As advertisements set the bar higher and higher, finding new problems to resolve with new products, the idea of having it all becomes a powerful subtext.

It's the ultimate problem for entrepreneurs to solve.

At the end of the day, how could you possibly feel complete when you don't have it all?

If you enjoyed reading this, please help me out by passing it on to other people who might appreciate it, sharing it through e-mail or your favorite social media platform. You can also follow me on Facebook and Twitter (@s_g_Carlisle).

Notes:

[i] Csikszentmihalyi, "The Costs and Benefits of Consuming," p. 270

[ii] Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, p. 14

[iii] Ibid., p. 662

Works cited:

Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly

2000. "The Costs and Benefits of Consuming." The Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 27, No. 2 (September 2000), pp. 267-272. It's behind a pay-wall, but if you have access to JSTOR, here's a link.

Tocqueville, Alexis de, J. P. Mayer, and Max Lerner

1966 Democracy in America. New York: Harper & Row.

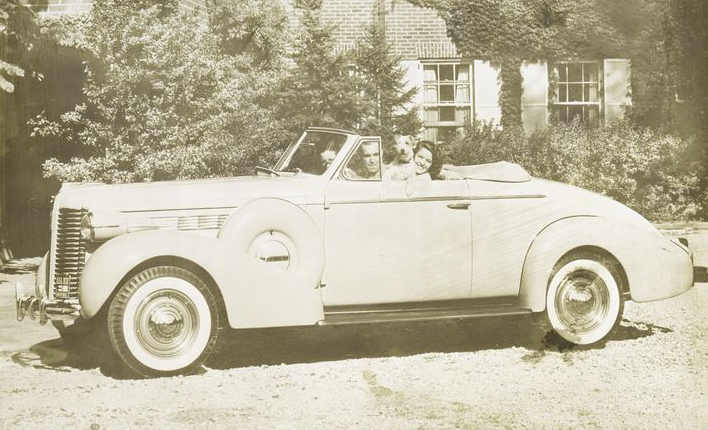

Image of 1938 Buick at top courtesy of the New York Public Library public domain collection.