Games Can Be Addictive. And Games about Identity? Even More

When people filled out their profiles on one dating website a few years ago they'd find this question:

"What do people notice first about you?"

A good 50% of the men on the site said "my smile," and left it at that.

In this way, they did nothing to make themselves interesting or distinguish themselves from everybody else.

I didn't want to fall into that trap myself when it came time to look on-line for love, so I went with the fact that several of my friends said that I looked a lot like Clark Kent when I wore my glasses.

This was a pretty good idea, apparently; it got me a substantial amount of attention.

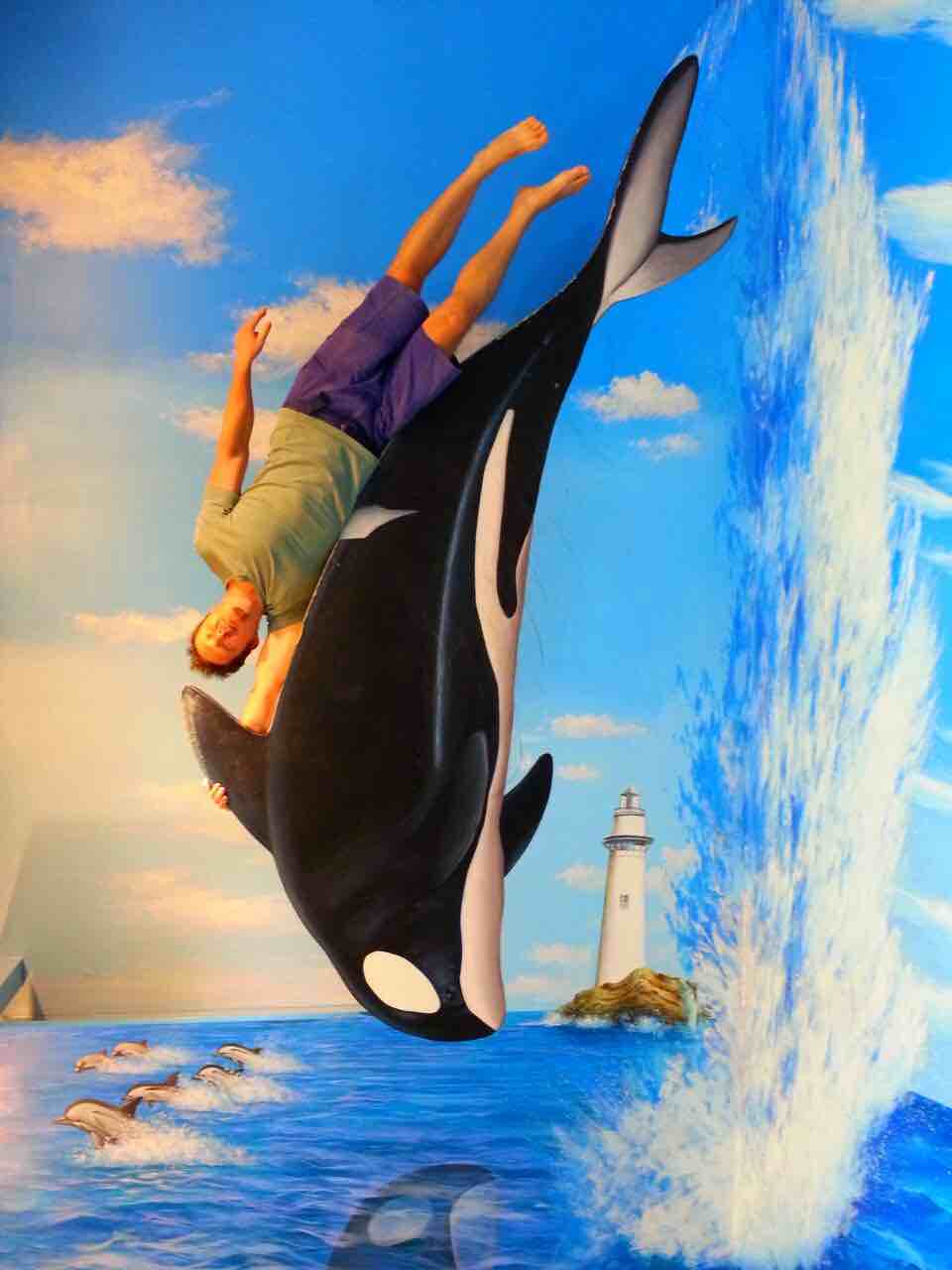

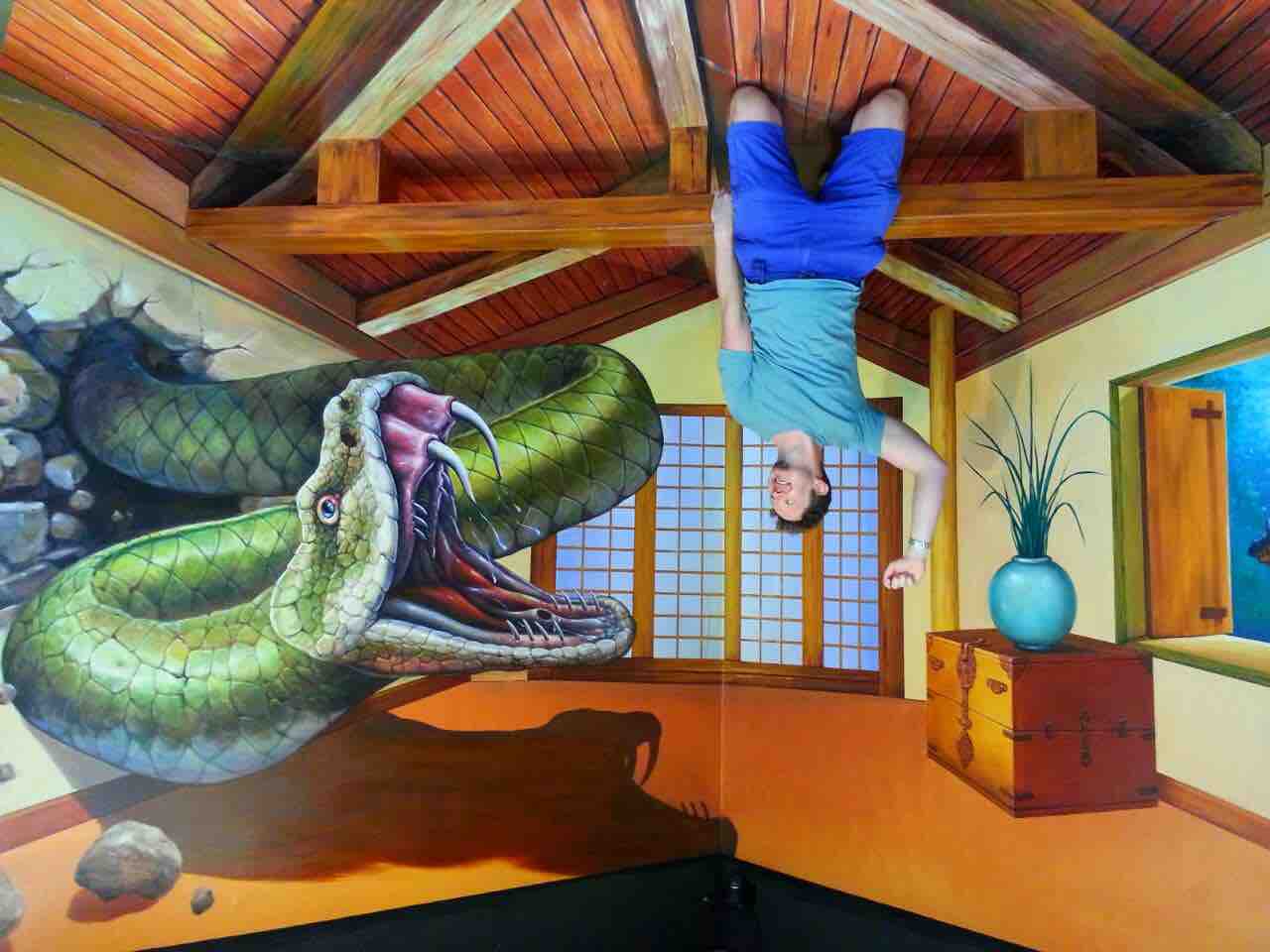

(The pics in this essay are from that profile, by the way.)

Because accruing wealth has become gamified in a way that provides regular hits of dopamine, and because that gamification connects to a person's sense of who they are, amassing wealth can become an addiction.

There are many gay men in California. But if you narrow it down to age-appropriate men with compatible sensibilities who happen to be single, conveniently located, and looking on-line at any particular time, the group is small enough that you can exhaust the supply rather quickly.

After dating around for a month or two, and meeting a number of very nice men I didn't want a relationship with, I decided to stay on the site.

In part this was because new men appeared on a semi-regular basis. But also because I liked the attention I got from people who weren't really possibilities.

...so I Kept Going

Most days I'd get a notification that someone somewhere in the world had given me (my profile, really, but I read it as me) a gold star.

I paid $9.99 a month to find out who.

A college student and skin-care expert in Manila.

A 70-year-old retired minister just coming out in Reno.

There was a lawyer who was only in the market for very tall, blue-eyed non-churched Ph.D.'s. (He really hoped it would work out between us; there was one other option living in Oklahoma City, but after that the well was dry.)

Most of these men weren't sensible dates for multiple reasons – distance, age, at times we spoke none of the same languages.

But I stuck around for the better part of a year, strictly for the ego gratification I got from being noticed by people I didn't particularly care to meet.

Every now and then, I would log on in the morning and discover that no one had given me a gold star.

I found this very annoying. What are you dong to me, internet? I'd say to myself.

And, Where's my util?

Eventually, I began to wonder why I cared in the first place. I didn't like the person I was at those moments, valuing the gold stars I collected just for the sake of collecting.

At a certain point I signed off and never signed back on again.

After a day or two, I realized that I didn't miss it.

A site that was supposed to set me up with men to date morphed into a game that slowly grew stakes. It rewarded me - and when it didn't reward, it disappointed. Because it was so easy to win gold stars, and because it happened so often, it settled into my sense of self and stayed there.

Utils and Dopes and the gamification of You

I used the word util a few paragraphs back – something I picked up from my microeconomics class in college. It comes the word "utility" and refers to how useful – how good – something is to a person. The util is a unit of pleasure that a person gets from a "basket of goods," another memorable term from Econ 101. It was a useful idea at the time – you were likely to spend money on baskets that gave you more utils. The more of something you had, the fewer utils the next one would give you. Buying one toothbrush when your old one wears out is a good thing. Buying your forty ninth spare does not provide utils.

The util isn't a bad idea. It's a way of taking something that exists as a feeling in people's heads, and applying it to objects out in the world.

Times have changed since I took econ. For one thing, we've realized that there's another kind of product that doesn't work like toothbrushes with their incrementally declining utility. Your fiftieth gold star feels just as good as the first.

Why did it feel so good? Why do people talk so much about being addicted to things like the "likes" they get on social media?

People often go to words like dopamine, a neurotransmitter that gives you a hit of pleasure when it's released. If a unit of utility-derived pleasure is a util, then is a unit of dopamine-derived pleasure a dope? I'll go with that for now. (Yes, these words may refer to the same thing at times.) Dopamine has something in common with a util: it's a way of taking about a subjective experience that turns it into something that seems to exist objectively, outside of conscious influence, and immune to interpretation. By moving us directly into brain processes, talk about dopamine skips over mind processes.

Dopamine talk is a way of saying that we don't really have control over how our desires make us act, while stopping short of the logical conclusion that comes with that kind of neurotransmitter discourse: that we don't have free will. In other words, it's a friendly way to talk about determinism without actually admitting to it. We have a cultural problem with the fact that "free will" doesn't actually make a lot of sense. We don't really have good ways to acknowledge that the decisions we made in the past turn us into people who make decisions in the present.

Addicted to Me

Dopamine and addiction are real things – there's no denying that. But brain processes don't happen in a vacuum. They relate to things we experience in everyday living: things like identities, intentions, interpretations, and decisions.

People refer to dopamine a lot when they talk about games and on-line behavior. When people get a reward – like an advantage in a game, or a gold star or certain number of views or likes – they get a dope: a little dopamine hit.

Sometimes when you play a game, you adopt a character.

Sometimes when the game involves popularity, the character you play is you.

For all the talk of the compelling nature of the internet, it's important to remember that you have to make a choice when we begin to link your sense of self to its games. Even when those choices end up being made unwittingly, it's still possible to step back and look at things from a different angle, to reevaluate the significance we place on different kinds of gratification, and decide what games a person wants to play.

Gamifying Identity

Gamification is the idea that anything can be made into a game. Last year, I wrote about how the Apple Watch gamifies fitness. Other apps gamify spending money on pizza and visiting websites. Gamification works by providing little dopes on a dependable basis. They encourage people to keep on playing – and, often as not, to toss dollars at the companies sponsoring the games.

For some activities, rewards become important as messages about self-worth. When this happens, they become compelling on an entirely new level. They gamify a person's identity.

That's what happened to me with those virtual gold stars. Except it wasn't pizza or calories burned that got gamified: it was my sense of myself as desirable.

Games can be addictive. Enough dopes from an app can get you to buy pizza even after the utils have given out. But when a game plays on someone's sense of self, it can end up distorting that person's perspectives and behaviors. (That's what I meant when I said that our past decisions can shape the identities that make decisions in the present.)

And when that distortion has to do with huge sums of money, it can mess everything – including countries – up.

It's Who You Know

I bring this up because, according to The New York Times, among the very, very rich, wealth ceases to be the source of necessities and luxuries. Instead, it becomes something of a point system in a never ending, all-consuming game. That's right - gamification can apply to your life's work. At least, that's the implication in Why Don't Rich People Just Stop Working?

The extremely wealthy, Alex Williams discovers, find it easier to multiply their money than the rest of us. This isn't necessarily because they're more skillful or more talented. Instead, they are tapped in to networks where wealth-generating opportunities arise regularly, where they have access to the cheap use of other people's money, and where they can link in to systems that are built to syphon money away from the other people's labor. If noting else, they have large sums of cash available to make bets on investments that most of us just can't afford to consider. It takes money, as they say, to make money.

And this, actually, is the root of the problem. Williams quotes hedge-fund manager Ray Dalio as he argues that capitalism

"is not working well for the majority of Americans because it’s producing self-reinforcing spirals up for the haves and down for the have-nots.”

(I, for one, find this gratifying; if you've read the rest of this site, you'll know that I'm dubious of what we call "meritocracy" in this country.)

To the immensely wealthy, the fact that even immenser wealth is out there doesn't mean that it simply falls into their laps. Williams points out that it takes a great deal of time and energy to snatch these ever more disproportionate rewards.

Money and Identity

And because the rewards are so great, it provides that compelling pleasure. At a certain point fairly early on in the wealth-amassing game, there comes a point where the next dollar can't actually buy anything you don't already have. But what it can do is act as a measure of personal worth. All the time paid off! I'm worthy of those lucrative connections! That is, immense wealth becomes a central source of identity – a sort of money-me.

And with this sort of gamification, just getting to the next level of wealth can be a huge source of dopes. In this case, it's not the money that matters - not he security it can buy or the comfort it guarantees. this is wealth beyond use - except for the dopes.

Realistically, there's a limit to the number of goals that can be scored in a professional soccer game, or good books an author can write. But money? The sky's the limit. So instead of competing against themselves or their personal records, the best these very rich people can do is to attempt to win against the people who are also competing against them.

So there's a competitive aspect to this, Williams explains. Just to top Paul Allen, Larry Ellison waited until Allen's 400-foot yacht was done and paid for before ordering his own 450-foot yacht. (Yes, 450 feet. One-eleventh of a mile, for a man who is 6'3" tip to toe, and probably about one foot from stem to stern.) There is always somebody you can one-up.

And it feels good.

People who are lucky enough to accept an invitation to this game often end up becoming the sort of people who are unable to leave it.

Because the gamification of accruing immense wealth provides regular hits of dopamine, and because that gamification connects to a person's sense of who they are, amassing wealth can become an addiction.

Joe Pinsker explored this phenomenon in an article in The Atlantic not long ago. He closes it with a conversation he had with author Gary Shteyngart, who did some research among the uber-rich for a novel he was working on.

The whole experience did not leave Shteyngart feeling good. Here were people who could purchase anything they could ever want and whose wealth was widely envied, and even they weren’t content.

Feel Bad for the Billionaires

But not too bad.

Those little shots of dopamine can come with a hefty price. What happens when billionaires decide to use their money to protect their fortunes just because having one feels so good?

Look at the system in place in the US today.

The quest for happiness often leads people down different paths to the gamification of their identities. This might explain the rich-guy push-back against things like proposals for taxes on extreme – what you might call excessive – wealth.

But the same billion dollars that can sooth the ego of the venture capitalist could also cure almost 12,000 cases of hepatitis C, a deadly disease with an effective but expensive treatment that remains out of he reach of a large percentage of sufferers.

Successes in these games are real, but they often become important only because of the dopes we attach to them. And this can cause us to overlook the fact that they may not do anybody any good otherwise.

“At the end of the day,” Shteyngart told Pinsker, “I was just happy to end this research, because it was quite depressing.”

Does this sound familiar?

If it does, then maybe it's time step out of the system. Quit seeking money if it only gives status. Stop looking for likes. I unsubscribed from the site that gave me gold stars, and went back to living my life.