Psychologist Abraham Maslow (1908-1970) first proposed what later came to be known as his Hierarchy of Needs in a paper entitled "A Theory of Human Motivation" in 1943. Here he is trying to explain what motivates people. The first level of needs must be met before rising to the second, the second level met before approaching the third, on up to the final fifth (or sixth) level. In and of itself, this isn't a theory of happiness, but it does serve as a description of what Maslow and his many, many followers think makes a person feel good. As a result, he builds an implicit theory of happiness embedded in the assumptions it makes. Moreover, it is often used as a justification for the pursuit of self-actualization, commonly considered the pinnacle of the pursuit of happiness.

The Stages

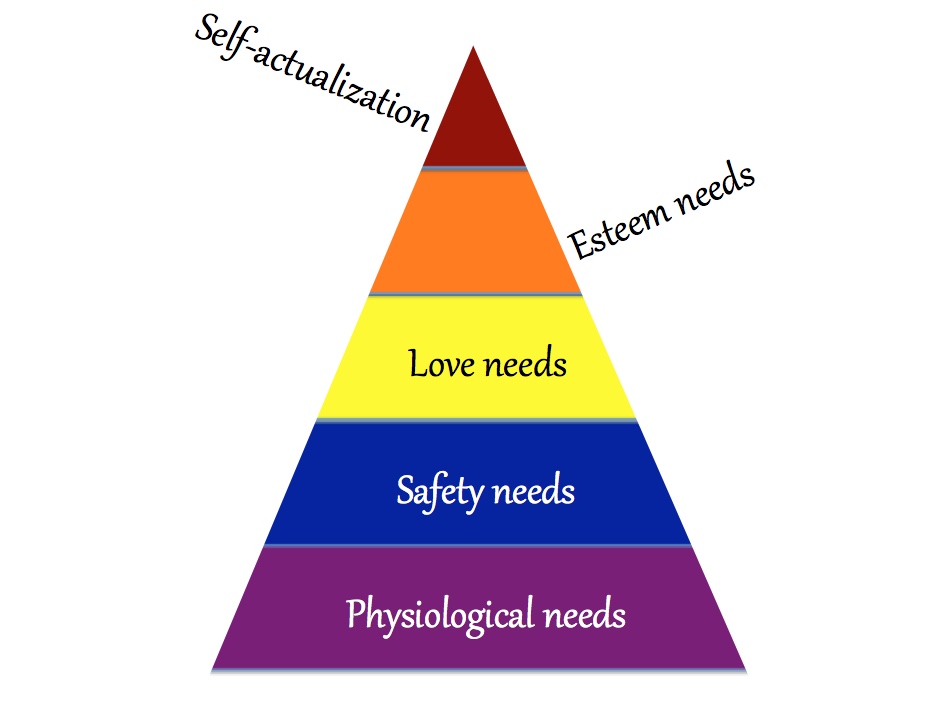

The stages in the hierarchy, from most basic and primary to the highest, are these:

- Physiological needs: the stuff you move in and out of your body that keeps biological systems running smoothly and the individual feeling sated.

- Safety needs: security, protection from dangers like intense weather, hunger, marauders and wild animals. Interestingly, Maslow asserts here that small children need some "rigidity" to help structure their lives. (p. 377)

- Love needs: "friends, or a sweetheart, or a wife, or children." (p. 381) Or, what the heck, maybe a husband. Or possibly just good friends.

- Esteem needs: both self-esteem and the respect of others. Maslow cites

the desire for strength, for achievement, for adequacy, for confidence in the face of the world, and for independence and freedom. (p.382)

- The need for self-actualization: "What a man can be," Maslow wrote in 1954, "he must be." This is the fulfilling of one's personal goals, or the satisfaction of the process of trying to fulfill them. (This distinction is important, but it becomes rather nebulous – different authors approach it different ways.) It's worth pointing out that, in 1943, Maslow found relatively few people who had achieved self-actualization, largely as a result of economic and social challenges. (This article was originally published during the Second World War, of course, which followed the Great Depression.) In those days, what a man can be might not end up being what he becomes.

Maslow's "hierarchy" has been widely and popularly misinterpreted. But like many popular misinterpretations, it plays an important role in American culture.

The hierarchy is usually (but not always) presented in the form of a triangle divided into five parts, the dimensions of which are determined by the amount of space the phrase "self-actualization" takes up in the top segment.

We can look at Maslow's list of motivations in two ways: the simple way, and the more complex way.

The More Complex, More Accurate Way

As I pointed out, the hierarchy isn't really a hierarchy. Maslow himself mentions a number of situations in which people satisfy higher-level needs while neglecting those below. Some of the reasons are personal and individual – artists so driven to produce that they forget to eat. Some are broadly cultural – people sacrificing nutrition and pleasure during Lent for the sake of knowing they are good Christians. There are so many possible exceptions beyond the ones he mentions that, even for people who live in societies structured like Maslow's, the odds are good that any one person will organize their needs in a slightly different order from the one Maslow suggests.

And in other societies, where people understand their needs differently, the hierarchy may look more like Maslow's jumble, or his need-heap. As I have explained elsewhere, my friends in Thailand think of themselves as members of a hierarchy. Their commitment to their places in society – as sons and daughters, parents, employers or employees, as younger or older than the people they know – all shape the ways they think about their interactions. Every loving relationship, then, is also hierarchical. So while we in the west separate out our love needs from our esteem needs, for Thais that distinction can get so blurry as to make the levels indistinguishable.

What Does This Mean?

It means that Maslow's Hierarchy does a couple of different things in place of what it's supposed to do:

- It's a useful heuristic for thinking about your own needs, if you are willing to play around with it and recognize that your needs may not conform to the rigid triangle that often appears at the tops of articles about it.

- It's also something of a cultural Rorschach test. It can help us understand how people in communities that put a lot of value in the hierarchy think about their needs.

This sort of ink-blot test involves taking the "hierarchy" as an actual hierarchy – something that many Americans do, for good cultural reasons. What they give up in accuracy and sophistication they gain in a certain way of understanding who they are. This, then, brings us to the simple way of reading the hierarchy.

The Simple Way: Maslow's Hierarchy as Cultural Rorschach Test

The simple way basically involves recognizing Maslow's list of needs as an actual hierarchy. His theory has come under criticism by people who recognize that needs don't actually form a rigid hierarchy. This seems quite unfair, as Maslow expends a good deal of ink discussing this very fact in his original article. He repeats the idea later on in his book on the topic, and its revision. However, this simplification has become stuck in the public consciousness.

When people draw firm lines between the stages, it becomes possible to think of them as distinct in nature. Maslow often called the first four levels "deficiency needs," arguing that, when they go unfulfilled, people often experience a sense of lack. He calls the needs in the top level, self-actualization, "growth needs." A person can live a fine life without having them fulfilled, but growing as a human being feels good.

Not Entirely Accurate, But Culturally Important

A need is a need, no matter its level. "The goal in Maslow's theory is to attain the fifth level or stage: self-actualization," writes the author of the top Google entry on Maslow's hierarchy – its Wikipedia page. In general, when people use Maslow's hierarchy in the simple way, the focus is on that top level. Using the hierarchy to think about needs allows them to consider the desire for self-actualization to be something natural. They can use this to combat the ideas that pursuing one's dreams (majoring in drama, or spending long afternoons painting landscapes down by the river) is selfish, narcissistic, or impractical.

As a result, people often use it as a device for framing conversations about an important tension in American society. As Maslow pointed out in 1943, few people were able to pursue self-actualization. In the 21st century, however, more people have such opportunities. At the same time, satisfying the "deficiency needs" can still be challenging, and worrying. Conflicts erupt between, for example, parents who want to their children to satisfy lower-level needs – by drawing a secure income from a job that may not be especially interesting – and children who want to pursue self-actualizing professions and projects, even if it means giving up a certain amount of security. (And, of course, there are children who want to settle down and lead more consistent lives while their parents pursue their dreams. The possible permutations go on and on.)

This simple reading of Maslow's approach can be important in contexts like these. It takes what some people see as frivolous desires and reinterprets them as needs, giving the want for things like a meaningful career a value on par, arguably, with the hope for a good income.

Maslow's hierarchy, then, can be seen as giving people permission and justification to follow their hearts. They can take the pursuit happiness, in the form of self-actualization itself, as a need that deserves to be satisfied. Maslow's work may remain popular, so many years after his death, because it provides a solution to the tension, in American culture, between the duty to satisfy lower-level needs, and the desire to pursue self-actualization.

Self-Transcendence

Toward the end of his life, Maslow added another concept to the end of his list: the need for self-transcendence, a sense of belonging to something larger than oneself. After people find self-actualization, he wrote, they often look for experiences that transcend the sense that they are discrete individuals, and try to experience the sense of being part of a larger whole. Maslow cites mystical experiences, and a sort of falling into transcendent states through the experience of truth, or beauty, or goodness. This sense of participation in something greater can also be accomplished in different ways, including selfless service.

This stage rarely appears in the diagrams of the hierarchy, though. Why is this? Marc Koltko-Rivera presents a number of possibilities in his comments on this last level. Just as Maslow formulated the idea, he became very busy (having been elected to the presidency of his professional association and doing a lot of lecturing at different universities), then very ill, and then dead. He may not have had the time to promote this version of his ideas adequately, or spread it broadly enough. One of the main expressions of these ideas was accidentally left out of the collection in which it was supposed to be published. Further, Maslow never ironed these ideas out to fit them seamlessly into his theory. And many psychologists were uncomfortable with the direction Maslow's thought was taking toward the end of his life.

From a cultural point of view, I would like to add one more reason why self-transcendence is often overlooked. It's possible that that this is because it doesn't blend easily with American stories about happiness. Most of them put self-actualization at the peak, making care of the self and the strengthening of individual identities - and sometimes even self-indulgence - the final goal.

Many people, then, seem uncomfortable and confused by the idea that going beyond the self could be a source of happiness. Moving away from the victories that come with a strong sense of individualism can appear to be a retreat from happiness rather than a leap into it. This makes sense if we look at the hierarchy as a cultural Rorschach test, but the addition of this extra level certainly doesn't harmonize well with the simple model described here.

Whatever the case, self-transcendence requires a different way of thinking about what it means to take care of oneself. When people disagree over whether they should pursue lower-level needs like financial security or self-actualizing dreams that don't pay well, adding this extra level – one focused on self-sacrifice and the nebulous concept of transcendence – doesn't mesh easily with either side's agenda. In other words, the spot for this idea in America's cultural landscape is still rather small.

But then, what does it say about Americans when they overlook the possibility that highest needs involve giving of, rather than actualizing, oneself?

For more on Maslow's Hierarchy, visit Maslow's Hierarchy is Probably Not What You Think.