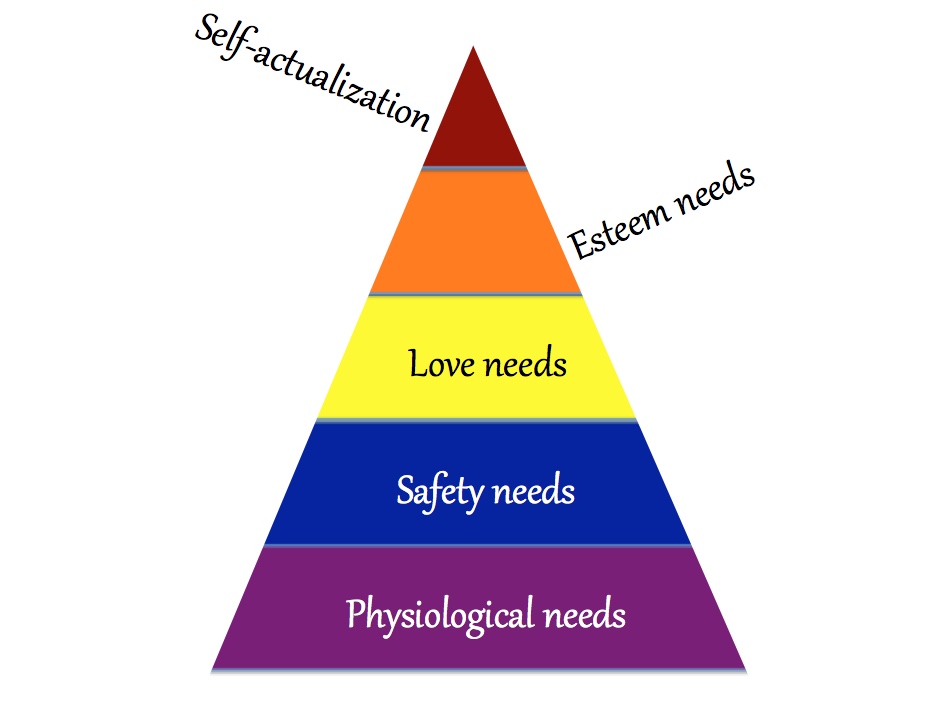

If you look for information on happiness for a little while, you will eventually come across a chart showing Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs. And if you look around for long enough, you'll come across hundreds them.

They look a lot like this:

Look at the lines! See how they divide the stages clearly from one another!

And notice how parallel they are, in a way that suggests a true hierarchy!

Check out the colors, which imply that each stage is distinct!

Maslow did develop five categories of human needs. Physiological needs are the most basic, and self-actualization needs constitute the final set. And Maslow does, in fact, write that he lays them out in a hierarchy.

But there's more to Maslow's Hierarchy than this.

If you take a look at the original article in which he described his approach, you'll find something a bit different from the quick, easy heuristic people frequently talk about today.

After a brief discussion of the nature of human motivation, and an attempt to fit his approach in with the existing literature, he defines five different categories of need:

those sharp lines and bright colors demarcating the categories, the clean and simple layers of even thickness – these are a wish list, the expression of a hope that the mind can be understood easily, and happiness approached by climbing this colorful ladder.

Maslow's Hierarchy:

- Physiological needs: the stuff you move in and out of your body that keeps your systems running smoothly and feeling sated. People will do anything for oxygen when they lack it, and almost anything for chocolate.

- Safety needs: security, protection from dangers like intense weather, hunger, marauders and wild animals. Interestingly, Maslow assert here that small children need some "rigidity" to help structure their lives. (p. 377) In some societies, protection from the extremes of poverty is seen as essential to a sense of safety. In others it is not viewed as a basic need that the community is responsible for.

3. Love needs: "friends, or a sweetheart, or a wife, or children." (p. 381)

4. Esteem needs: both self-esteem and the respect of others. Maslow cites:

the desire for strength, for achievement, for adequacy, for confidence in the face of the world, and for independence and freedom. (p.382)

There's a footnote to this one, though. He wonders if all these esteem needs are universal. I'd say that, by this point in the 21st century, it's pretty clear that it depends on the person and the culture.

Then finally:

5. The need for self-actualization: Singer's got to sing, swimmer's got to swim. Some things make a life feel full.

When people have satisfied the needs in one category, the move on to the next. Once you've got enough food, you look for shelter. Once you've got good protection, you look for love, on up to the top.

But:

This only brings us half way through the article. Much of the rest is committed to laying out exceptions to the rules he's just defined. People may not satisfy their needs in the order described if:

- They are very poorly adjusted to their circumstances, and can never move beyond the most basic satisfactions

- They are very well adjusted, and don't worry about some of the lower ones, like the need for esteem, before pursuing things like self-actualization. They just expect those needs to be satisfied

- They are so deeply creative that they will ignore basic things like hunger while they write or paint or play because they're so driven to produce self-actualizing work

- They conform fully to the mores of their societies, which place fulfilling certain duties above basic care for the self

There are other exceptions, too.

In other words, Maslow's Hierarchy isn't really a hierarchy.

It's a heuristic.

That is, it's a set of categories that people often deal with in a particular order, but they don't have to do it that way. It might be useful to think with, in a broad, general way, but recognizing exceptions is just as important as noticing the rule.

Not only that, the categories sometimes blur together. For example, some people believe that only people who are strong and respected can be loved, Maslow writes. These people seek esteem along with love.

Maslow's Heuristic

Maslow finishes off his list of caveats with this:

Perhaps more important than all these exceptions are the ones that involve ideals, high social standards, high values and the like. (p. 387)

In other words, this isn’t about universal human needs. It has a lot to do with the cultural environment in which a person learns what her needs are, and which ones are the most important.

Why Does this Matter?

Because Maslow isn't really telling us what we need as human beings. He's giving us a tool to explore the way we break down and organize our needs. It's a mirror to look at the ways we think about what we want.

And the ways we do this are going to be connected to our cultural worlds.

Something consistently strikes me when I talk to my friends in Thailand or watch Thai shows online. With every sentence – literally – people are positioning themselves in their relationships. A lot of this has to do with the ways Thais say "you" and "I." Where we stick with one word for each in English – one word that works for every occasion – Thais have a plethora. Each version of "I" or "you" suggests something different about the relationship.

Figuring out the difference between phi and nong is essential in close relationships when people speak Thai. Phi means "elder" or "senior." Nong is its junior counterpart. Every phi has a nong, every nong a phi. But something else comes with that age difference. A certain amount of authority goes to the phi, and a certain amount of care is aimed at the nong. In other words, being a part of a close relationship, one that satisfies the need for love and acceptance, involves entering into a hierarchy. Using those words is about both love and esteem.

So social and esteem needs are very hard to separate there, as they are, I suspect, in most societies influenced by Confucian thought. Confucius laid out the idea that humans are human in relation to other people. Your sense of "you" depends on who you're relating to at the moment. Different needs and responsibilities play in to different sorts of connections. You can be a daughter, a sister, and an employee all at the same time, but each of those relationships comes with its own set of roles. Social needs and esteem needs, for the most part, get rolled up together here.

So, What About Us?

Why do Americans tend to separate social needs from esteem needs? I suspect it has to do with the same reason we use "I" and "you," and not a dozen other more nuanced words when we talk to one another. Americans tend to see themselves as separate from one another. I'm the same "I" no matter who I'm talking to. Most Americans don't really like to see themselves as part of a hierarchy (even when they are) and they often resist the idea. As a result of this general tendency to think of ourselves as individuals, we often distinguish between esteem needs and social needs.

At the same time, I suspect that Maslow's hierarchy isn't exactly changing in the US, but diversifying. The integration of smart systems into everyday life is changing our values systems along with everything else. The use of social media seems to be altering how many people think about self-actualization. Being liked by others on-line – what used to be an esteem or love need – is now top of the chart for them. That said, many of the people I like and respect the most just don't have time for it. Many of them are busy enough with their own self-actualizing projects that they don't need to be esteemed by others – at least, not this way.

This Happens A Lot with Self-Help...

Why have we taken something that Maslow intended as a rather loose heuristic with all sorts of exceptions and turned it into a rigid rubric for talking about happiness? I suspect that it has a lot to do with the culture of self-help, which often looks for easy answers meant to satisfy everyone. It's easy to mistake "Maslow's hierarchy" for an actual universal hierarchy if you don't read his article. It's there in the name we've given it, after all. (The article is actually called "A Theory of Human Motivation," by the way. The idea that it might be a hierarchy only appears several pages in.)

In the rush to find broadly-applicable solutions, there's a tendency to look to the universals of pop psychology rather than to the vagaries and complexities of what happens when cultures and minds interact. There is also a desire to make happiness a product of the mind and not of the world at large. The mind, after all, is under our control, at least in theory. The world around us specifically is not.

This isn't true of psychology in general. But a lot of the popular literature on happiness, which usually takes a psychologically informed approach, wants to put happiness in the head, and not out in the world around us.

And why not? As the Buddha argued twenty five hundred years ago, you can't fix the world – you can only fix yourself.

What many 21st century seekers overlook is the fact that the outside world is always there inside us, too. (The Buddha's plan for finding enlightenment – which can take decades of work to complete – involves getting rid of the sense of self that's influenced by outside forces.)

So this, I suspect, is where the idea behind "Maslow's Hierarchy," instead of his Heuristic, comes from.

It's not an accurate description of the ways we go about prioritizing the things we need. No, those sharp lines and bright colors demarcating the categories, the clean and simple layers of even thickness that typify images of Maslow's hierarchy – these are a wish list, the expression of a hope that the mind can be understood easily, and happiness approached by climbing this colorful ladder.

What Next?

It's fairly likely that you belong to one of those exceptions that Maslow described in his original article; if not, you might well have an exception in your own way that Maslow didn't mention. Probably the most sensible thing to do, then, is to look to yourself, and how you interact with the people and things around you, and make your own hierarchy of needs.

Instead of imagining that Maslow got it right (he never made the claims that later users of his chart have), you can use it as a point to jump off from, as an imperfect guide for self-reflection. Is self-actualization really the last need you'll satisfy, or is it more important than esteem? (For me it certainly is – I keep writing these essays because I enjoy working through these ideas, although even my mother doesn't usually read them.) Do you always put your biological desires first, or do you take pleasure from exhausting exercise, or the willpower to diet?

Do these categories even work for you?