For those of us who weren't immediately in the path of the eclipse in August 2017, probably the most interesting thing about it was the reactions of the people who were. A few friends tried to explain the experience to me recently – they soon fell to describing one another's reactions because they couldn't do it justice by likening it to what I was familiar with. I listened, on the radio for a few hours, to reports from different spots as the moon transited in front of the sun: an intense experience. Transporting. Amazingly real. Transcendent. Indescribable for some – it was just a little bit beyond the words they have here in the 21st century. Did it connect those witnesses to God? Not for my secular friends – but in another time, from another angle, being confronted by nature's power this way might have felt like opening a window and seeing God.

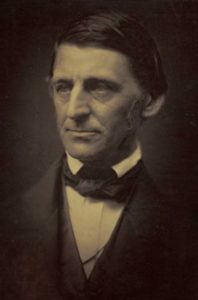

Written almost two hundred years ago, Nature is a reflection of its time, but the breezes that blow through American history have carried hints of Ralph Waldo Emerson's way of thinking to us today. In order to understand how Americans talk about happiness now, it's important to understand how he contributed to the conversation – or at least the way he participated in it, innovating as well as borrowing and amplifying the ideas of others. He manages to combine a couple of odd bedfellows: something similar to the Buddhist concept of no-self. with the search for one's own authentic self.

Emerson was a Transcendentalist – a member of a small American movement in the early 1800's which sought God as a visible motivating force behind the world. He was visible, that is, if one knew how to look. Emerson divided reality into two parts. The visible, material world is nothing more than a side-effect of a deeper spiritual reality: we should regard

nature as a phenomenon, not a substance; to attribute necessary existence to spirit; to esteem nature as an accident and an effect.[i]

Living Naturally

It's easy to get caught up in our material "reality," though, either through habit or because of the value people place on what we find in it.

But, Emerson writes, the good life – in fact, the goal of all human life – is to look beyond the physical world and see the underlying connections, the unity that reflects God.

Nature is the way to get there, to encounter God's truth. Out in nature, "I become a transparent eye-ball;" he writes. "I am nothing; I see all; the currents of the Universal Being circulate through me; I am part or particle of God."[ii] How can he achieve his ultimate goal? Through nature, once again. In its physical manifestation as the everyday world it gives us clues about how to live well, and this is the first step toward transcendent understanding.

So nature has lessons for our worldly lives as well as providing access to the deeper reality that transcends it. The human mind, he explains, is a reflection of nature. By giving us models to learn from, it teaches us to think; and since we use the same models, it gives us the languages through which we communicate:

The instincts of the ant are very unimportant, considered as the ant's; but the moment a ray of relation is seen to extend from it to man, and the little drudge is seen to be a monitor, a little body with a mighty heart, then all its habits, even that said to be recently observed, that it never sleeps, become sublime.[iii]

Ants give us aphorisms about hard work, but they also serve as an example, showing us, at least in some small way, how we should be. Nature can serve as a guide to finding one's own personal nature. By giving us the chance to learn to adapt to nature, and understanding how to read it, God reveals us to ourselves.

A Deeper Authenticity

But thinking, speaking, and relating to the world around us is both how we find our true selves, and how we lose them. Emerson has great distain for what passed for civilization in his day. Where Enlightenment characters like Ben Franklin placed a high value on community and cooperation, Emerson values independence. In a later essay called "Self-Reliance," he argues that everyone should follow his own heart. I'm using the masculine pronoun intentionally here – his vision of morality has a pronounced machismo to it.

Trying to get along with others for its own sake is pointless. He writes, "My life is for itself and not for a spectacle." He scoffs at attempts at cooperation and regularity for the sake of pleasing others. ("A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds.")[iv]

He's not much for charity, either – it wastes money on fools.[v]

Nature is a demanding master, he explains and it is up to us to stand up to its demands.

By 21st century lights, he appears to be quite selective about the lessons he takes here. Ants may be hard workers, but he doesn't see the fact that they're also cooperative conformists. The lessons he sees often involve the rewards of standing on one's own and not of working together, and build on individualistic form of reason more than the logic of compassion or empathy that you might find, for example, in Tibetan Buddhism.[vi] In this, Emerson is part of a long tradition. His individualist flavor is still apparent in our conversations about happiness today.

So the experience of an eclipse – or experiences more ordinary, like the busy quiet of a mountain forest after the rain, or sunlight glinting off a stream – is transporting today, just as it was in Emerson's time. But what we make of it is different. Although people do not interpret it as an experience of God as often as they used to, the implications of Emerson's idea still ramify through American visions of the world.

Extra Credit

(This is for students of the history of ideas, and those taking as-yet-uninvented Happiness Appreciation classes.)

American culture isn't one thing. It isn't even a set of things, comprised of all our subcultures. Instead, it's a messy, cross-cutting hodge-podge of values, stories, ideas, ideals, and habits. Sometimes they work in harmony with one another, but often they're at odds. (The apparent wholeness that "culture" suggests is the reason that most anthropologists – people who often describe themselves as professional students of culture – have largely given up on the word.) American theories about happiness are as confused and mixed up as anything else in our social environments. Emerson's Nature echoes the visions of some of the Romantics in England, France and Germany,[vii] and it reflects a response to ideas about happiness – based on ideals of comfort, community, and benevolence – that made their marks during the Enlightenment.[viii] One can only find God by oneself, he explains, setting aside the social norms that were so important to enlightenment thought in favor of perception, and one can only find oneself through God.

Another contribution to American conversations about happiness appears in Emerson's essays: the notion that happiness comes from seeking one's authentic self. In the west, after the Protestant Reformation, there has been a long project of redefining humanity's relationship with God. Where Catholicism set the clergy and the Pope between God and the people, Protestants sought a way for individuals to connect directly to the divine. Enlightenment philosophers generally saw a connection through our reactions to the physical world – our desires and rational responses to human conditions opened that window onto God's will.

If the Enlightenment sowed the seeds of democracy through the idea of universal rationality, then the Romantic era which followed it (and which, in the US, spawned the Transcendentalist movement) left a different sort of legacy: the idea of an authentic self which grew from the idea of a universal soul. Instead of finding God instance by instance, God could be found through a sense of transcendence. The goal was to strip away those elements of cultural rationality and social-mindedness that prevent people from expressing their inner sparks. Finding out true selves, it seems, and living ourselves authentically, makes it easier for us to connect to God, from whom the material universe emerges.

For me, having spent a number of years in Thailand, this is especially interesting because of the way it mirrors some aspects of Theravada Buddhist thought without actually coming to all the same conclusions. I read Emerson's desire to be a "transparent eyeball" as similar to the Gautama's desire to find enlightenment – seeking reality through perception unadulterated by thought. But where the Buddha (at least in the Theravada tradition) saw the only route to enlightenment through removing all desires, Emerson sees drawing out the right ones to focus on as key. Where the Buddha said that enlightenment could only be reached by giving up the idea that one has an essential self, Emerson saw enlightenment as coming through it. The Emersonian habits of thought around the idea of an "authentic self" that so many Americans hold dear may be part of the reason that Buddhist ideals – not to mention many modern psychological conceptions about the malleability of the mind – can be such a hard sell in the US.

There's also a very common trope explored here, and repeated many times after – what I suspect is part of America's Romantic heritage: you can only find yourself by losing yourself. For now, I'm calling this the Claude Rains paradox.

If you enjoyed reading this, please help me out by passing it on to other people who might appreciate it, sharing it through e-mail or your favorite social media platform. You can also follow me on Facebook and Twitter (@s_g_Carlisle).

[i] Nature, chapter 6

[ii] Nature, chapter 1

[iii]Nature, chapter 4

[iv] First Essays, "Self-Reliance"

[v] "Then, again, do not tell me, as a good man did to-day, of my obligation to put all poor men in good situations. Are they my poor? I tell thee, thou foolish philanthropist, that I grudge the dollar, the dime, the cent, I give to such men as do not belong to me and to whom I do not belong." Emerson, "Self-Reliance."

[vi] French, The Golden Yoke

[vii] Campbell, 1987.

[viii] Taylor, 1989.

Works Cited:

Campbell, Colin

1987 The Romantic Ethic and the Spirit of Modern Consumerism. London: Basil Blackwell Ltd.

Emerson, Ralph Waldo

1836 "Nature." http://transcendentalism-legacy.tamu.edu/authors/emerson/nature.html

1841 "The Over-Soul." Essays, First Series. https://archive.vcu.edu/english/engweb/transcendentalism/authors/emerson/essays/oversoul.html

1841 "Self-Reliance." Essays, First Series. https://archive.vcu.edu/english/engweb/transcendentalism/authors/emerson/essays/selfreliance.html

French, Rebecca

1995 The Golden Yoke: The Legal Cosmology in Buddhist Tibet. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Taylor, Charles

1989 Sources of the Self: The Making of the Modern Identity. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Image of Ralph Waldo Emerson at top in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia.